Modern-day skeptics propagate a new belief that Jesus is a fictional character and that there is no evidence that he ever existed. After a while, any historical figure can look like a myth, so that is why this belief is emerging now.

Did Jesus exist? Here you will find some historical evidence recorded by Roman historians and officials proving that Jesus did exist.

During the first and second century BC, the officials of ancient Rome and Judea, and the famous historians that followed questioned Jesus’ work such as raising people from the dead, healing, or his resurrection. These early-century skeptics, however, never questioned that he existed.

To find evidence that Jesus lived, let’s examine some historical sources outside the Bible. There is very little documentation remaining, unfortunately, for any person who was alive at the time of Christ. The majority of ancient historical documents have been lost through time because of wars, fire, theft, bad weather, and deterioration. Fortunately, there are a few archeological discoveries that have been made.

Some scholars date the birth of Jesus to 6 or 7 BC because Publius Sulpicius Quirinius was a Roman governor of Syria. However, he first became a governor in 6 or 7 BC and then got re-elected around 1 or 2 BC, the time that is recorded in Luke. Both the gospels of Matthew (the medical doctor) and Luke (the physician) record Jesus’ birth.

Many secular historians, such as Aristides the Athenian, Justin Martyr, Ignatius of Antioch, Hegesippus, Clement of Rome, etc., have mentioned Jesus’ name in their works. Nine early non-Christian secular writers in total mentioned Jesus as a real person within 150 years of his death.

If we want to consider both Christian and non-Christian sources, forty-two sources mention Jesus, compared to only ten that mention Tiberius. There are still various books and letters, preserved over many centuries, that provide evidence of the life of Christ.

Roman Historians

Historians in Rome kept detailed records of the people and events in the Roman empire. Since Jesus was not involved in the political or military affairs of Rome, there were only two Roman historians who mentioned Him in their writing, acknowledging Him as a real person: Cornelious Tacitus and Lucian of Samosata.

As a second-century theologian, Justin Martyr wrote:

Now there is a village in the land of the Jews, 35 stadia from Jerusalem, in which Christ was born, as you can ascertain also from the registries of the taxing under Cyrenius your first procurator in Judea (First Apology, chapter 34).

Martyr’s records confirm Jesus’ birth in Judea, but Martyr was a theologian, thus skeptics don’t accept his account as valid proof that Jesus existed.

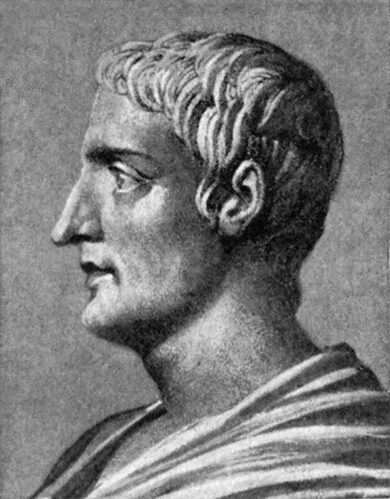

Cornelious Tacitus

Gaius Cornelius Tacitus

via Wikimedia Commons

Tacitus would judge and punish those whom he found guilty. His historical records confirm that Jesus’ crucifixion was done by Pontius Pilate.

In Tacitus’ The Annals of Imperial Rome, he recounts the major historical events from the years shortly before the death of Augustus up to the death of Nero in AD 68. His work mentions Christus (Greek word for Christ) who lived during the reign of Tiberius and was executed by Pontius Pilate.

Tacitus wrote the following:

Consequently, to get rid of the report (Great Fire of Rome), Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judea, …but even in Rome… (The Annals of Imperial Rome, XV, 44).

Book XV of Tacitus’s Annals was kept in the 11th to 12th-century Codex Mediceus II, a collection of medieval manuscripts located in the Bibliotheca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence, Italy. The following quote confirms that Jesus was the founder of Christianity, originating in Judea and later spreading to Rome:

… whom the crowd called ‘Chrestians.’ The founder of this name, Christ, had been executed in the reign of Tiberius by the procurator Pontius Pilate …” (Codex Mediceus 68 II, fol. 38r, the Bibliotheca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Italy.)

The 4th-century emperor, Julian the Apostate (so-called because he rejected Christianity after being raised in it) wrote:

Jesus, whom you celebrate, was one of Caesar’s subjects. If you dispute it, I will prove it by and by; but it may be as well done now. For yourselves allow, that he was enrolled with his father and mother in Cyrenius…But Jesus having persuaded a few among you, and those the worst of men, has now been celebrated about 300 years; having done nothing worthy of remembrance; unless anyone thinks it is a mighty matter to heal lame and blind people, and exorcise demoniacs in the villages of Bethsaida and Bethany (Cyril Contra Julian, VI, 191, 213).

Many New Testament scholars date Jesus’ death to about AD 29. Pilate governed Judea in AD 26-36, while Tiberius was emperor in AD 14-37.

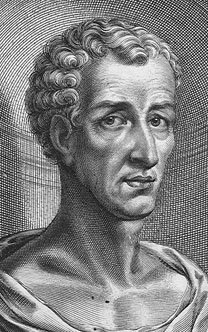

Lucian of Samosata

Lucianus by William Faithorne via Wikimedia Commons

Lucian of Samosata (c. 115–200 C.E.) was a Greek satirist and author of The Passing of Peregrinus.

Lucian was a former Christian who later became a famous Cynic and revolutionary.

Lucian was a secular writer who most likely obtained all his information from sources independent of Christian doctrines and New Testament books.

His statements are separated from theological doctrines and serve as independent evidence of Jesus’ life and His crucifixion by the Romans.

While writing a biography, Lucian made a satirical reference to Jesus in two sections of Peregrinus without mentioning his name:

It was then that he learned the marvelous wisdom of the Christians, by associating with their priests and scribes in Palestine. And— what else?—in short order he made them look like children, for he was a prophet, cult leader, head of the congregation and everything, all by himself. He interpreted and explained some of their books, and wrote many himself. They revered him as a god, used him as a lawgiver, and set him down as a protector—to be sure, after that other whom they still worship, the man who was crucified in Palestine because he introduced this new cult into the world. For having convinced themselves that they are going to be immortal and live forever, the poor wretches despise death and most even willingly give themselves up. Furthermore, their first lawgiver persuaded them that they are all brothers of one another after they have transgressed once for all by denying the Greek gods and by worshiping that crucified sophist himself and living according to his laws.” (In Lucian Selected Dialogues; translated by Craig A. Evans)

In Lucian Volume V, Lucian makes comments and criticisms of historical events. He was highly critical of other writers who distorted history to please their masters or filled historical gaps with their personal narratives.

He wrote, “The historian’s one task is to tell a thing as it happened. He may have private dislikes, but…” (06:44)

Lucian had a proven track record of historical accuracy and verification. He believed Jesus was just an ordinary man who lived his life, healed the sick, and preached. He never described Jesus as God or a divine entity, nor did he deny anywhere that Jesus existed.

Roman Officials

There were at least six Roman government officials who mentioned Jesus’ name and his followers in their letters.

Pliny the Younger and Emperor Trajan

Pliny the Younger

via Wikimedia Commons

Pliny the Younger was a lawyer, author, and imperial magistrate under Emperor Trajan (AD 56-117).

In AD 112, Pliny wrote a letter to Trajan about his desire to force Christians to reject Christ and worship Roman gods or Caesar instead. In the letter, he was asking Emperor Trajan for counsel on dealing with Christians.

Pliny had never done a legal investigation of Christianity, so he consulted Trajan on what he should do next. In his letter, Pliny states that Christians worship Christ as if He was God Himself, and they don’t worship the gods of Rome. During that time, many Christians were persecuted for their faith, and there is a lot of evidence about Christ that has been preserved to the present time:

They (the Christians) were in the habit of meeting on a certain fixed day before it was light, when they sang in alternate verses a hymn to Christ, as to a god, and bound themselves by a solemn oath, not to any wicked deeds, but never to commit any fraud, theft or adultery, never to falsify their word, nor deny a trust when they should be called upon to deliver it up; after which it was their custom to separate, and then reassemble to partake of food but food of an ordinary and innocent kind. (Pliny the Younger)

According to the early historians, Jesus’ great-nephew, other relatives, as well as associates of the original apostles, were alive. They could easily verify His existence. The early authors often referenced existing documents as well, that have since been lost, such as trial records or records of His birth.

Aulus Cornelius Celsus

Aulus Cornelius Celsus by Pierre-Roch Vigneron

via Wikimedia Commons

Celsus was a 2nd-century Greek philosopher who criticized early Christianity. He was the author of ‘On The True Doctrine’, which survived exclusively in quotations in Contra Celsum, a refutation created in AD 248 by Origen of Alexandria.

‘On the True Doctrine’ was written in AD 175 to 177 and is the earliest known comprehensive criticism of Christianity. It was written when Christianity was growing, during the reign of Marcus Aurelius.

Celsus was interested in ancient Egyptian religion and knew Hellenistic Jewish logos theology. He wrote many statements disproving the divinity of Jesus, saying, “Jesus performed his miracles by sorcery,” but he never denied Jesus’ existence.

He acknowledged that Christians were successful in business. He wanted them to be good citizens and retain their own beliefs, but also worship the emperors and join their fellow citizens in defending the empire.

In The Early Christian World, Volume 2 by Taylor & Francis, Celsus does not deny Jesus’ miracles but rather focuses on how they were performed. Using rabbinical sources, Celsus attributes Jesus’ miracles to great magical skills:

Jesus, on account of his poverty, was hired out to go to Egypt. While there he acquired certain [magical] powers… He returned home highly elated at possessing these powers, and on the strength of them gave himself out to be a god…It was by means of sorcery that He was able to accomplish the wonders that He performed… Let us believe that these cures, or the resurrection, or the feeding of a multitude with a few loaves…These are nothing more than the tricks of jugglers…It is by the names of certain demons, and by the use of incantations, that the Christians appear to be possessed of [miraculous] power…. (The Early Christian World, Volume 2 by Taylor & Francis)

Celsus tries to dismiss miracles performed by Jesus, calling them illusionary tricks. He then offers another explanation, calling the miracles “demonic possession”. He believed that Christians themselves invented the virgin birth story and the divinity of Jesus.

Instead of denying the alleged events, however, Celsus offers his own alternative theories. He writes that Jesus came from a village in Judea and was the son of a Jewish woman. She was convicted of adultery with a Roman soldier and was turned down by her husband, a carpenter by trade.

There was a similar passage written in the Jewish Talmud, so Celcus likely used religious sources for some of his arguments. Celsus concludes that Jesus was merely a man, not a god. Even though Celcus denies Jesus’ divinity, he never denies his existence.

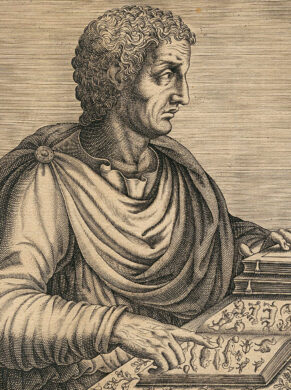

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus

via Wikimedia Commons

Suetonius (AD 69 to 130) was a major Roman historian who recorded the life of Roman rulers such as Julius Caesar and Domitian. During his lifetime Suetonius served as a director of the imperial libraries and then a private secretary to Hadrian.

Unfortunately, the majority of his books are lost and only a few have survived.

Suetonius also mentions Jesus in his work:

As the Jews were making constant disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, [Claudius] expelled them from Rome.” (Life of Claudius 25.4)

While it is not clear whether Suetonius refers to Christ himself in this quote or uses the original Latin word Chrestus as a title, there were seven uses of the word Chrestus in the New Testament, found in Mt 11:30; Lk 5:39, 6:35; Rom 2:4; and 1 Cor 15:33, where authors traditionally associated God with Chrestus meaning good Lord.

The vast majority of Christian authors, such as Tertullian, use the name Chrestus when referring to Jesus. Tertullian (Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus) was an early Christian writer who lived in the Roman province. Despite being conservative, Tertullian originated new doctrinal concepts and advanced the development of the early Church doctrine.

In his writings, he states that the name Chrestus was not spelled correctly, even if it relates to the name of the founder of Christianity.

Thallus

Thallus.

Image by jesusskeptic

The work of Thallus (around AD 52) was preserved only in fragments. Similar to other accounts, he mentions a “midday darkness” event that occurred during the crucifixion of Jesus on the Passover.

Secular historians, such as Julius Africanos and Phlegon van Tralles, also wrote about a solar eclipse event, thus providing confirming evidence during the reign of Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus.

There was a debate among secular historians trying to explain the phenomenon. Some tried to prove, in scientific terms, that the event occurred naturally, while others argued that it was a supernatural event, saying a solar eclipse couldn’t physically occur during the full moon due to the position of the planets.

Mara Bar-Serapion

Mara Bar-Serapion (AD 70) resided in the Roman province of Syria and was a Syriac stoic philosopher. The records reveal that he was neither a Jew nor a Christian, and probably worshipped pagan gods. He became famous through one letter he wrote to his son, Serapion Junior:

What advantage did the Athenians gain from putting Socrates to death? Famine and plague came upon them as a judgment for their crime. What advantage did the men of Samos gain from burning Pythagoras? In a moment their land was covered with sand…What advantage did the Jews gain from executing their wise King? It was just after that their kingdom was abolished. God justly avenged these three wise men: The Athenians died of hunger. The Samians were overwhelmed by the sea. The Jews, ruined and driven from their land, live in complete dispersion. But Socrates did not die for good. He lived on in the teachings of Plato. Pythagoras did not die for good. He lived on in the statue of Hera. Nor did the wise King die for good. He lived on in the teaching that He had given. (Mara Bar-Serapion, AD 73)

In this passage, he provides a summary of curses that people received for the persecution of the saints. He also confirms that Jesus preached the gospel of the Kingdom and was later crucified.

Jewish Historians

Roman historians and Roman officials were not the only people who mentioned Jesus in their writings. Some Jewish sources contain direct references to Jesus’ existence too.

Flavius Josephus

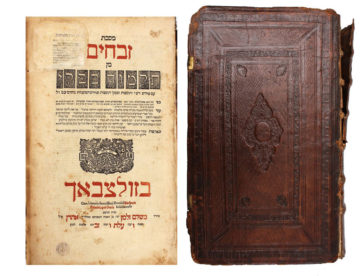

The Jewish War Book by Flavius Josephus.

Image by openlibrary.org

Josephus (AD 37-100) was a Roman-Jewish historian, scholar, and hagiographer who grew up as an aristocrat in first-century Palestine. In his book, Antiquities of the Jews, a 20-volume historiographical work, Jesus is mentioned twice.

In his other book, The Jewish War, he doesn’t mention Jesus at all. Any reference to Jesus was probably added by others at a later date and not by Josephus himself.

The first short reference to Jesus is found in the Antiquities of the Jews. He wrote about Jesus’ brother James, who was a leader of the church in Jerusalem. When the Roman governor was absent temporarily, the high priest Ananus executed James. As a result, Ananus later lost his position as a high priest.

Josephus wrote about the death of James and called him “the brother of Jesus who was called Christ” (Antiquities of the Jews, XX, 9, 1).

So [Ananus] assembled a council of judges, and brought before it the brother of Jesus, the so-called Christ, whose name was James, together with some others, and having accused them as lawbreakers, he delivered them over to be stoned. (Antiquities of the Jews, XX 9.)

There was more than one James in Josephus’ book, and he had to specify which James he was referring to. Jesus’ real name was Yeshua in Hebrew, Yeshua meaning salvation. The concatenated form of Yahoshua means Lord who is Salvation. He added the phrase “who is called Messiah”, or Christos in Greek since he was writing in Greek.

In the New Testament, James was called “the brother of the Lord” or “of the Savior.” The title “the brother of Christos” wasn’t used because there were many other people named Jesus. Also, this passage was not written specifically about Jesus. Jesus and his brother were not the primary focus here.

The longer passage in Josephus’s Jewish Antiquities (Book 18) refers to Jesus as the “Testimonium Flavianum”. There are several citations made by other existing authors, giving evidence that this document existed well before the 10th century

In the original work of Flavius Josephus, both passages testify that Jesus existed, performed “wonderful works”, had a brother James (James the Just), and was crucified by Pontius Pilate. Flavius was a high-profile historian who verified his information and most likely interviewed the apostles himself.

The Babylonian Talmud

The Talmud, old rabbinical literature, refers to a “Yeshu of Nazarene” who was “hanged” (a Jewish idiom for crucified) on the eve of the Passover:

The Talmud, old rabbinical literature, refers to a “Yeshu of Nazarene” who was “hanged” (a Jewish idiom for crucified) on the eve of the Passover:

On the eve of the Passover Yeshu was hanged 40 days earlier before the execution date. Before the execution event, Herod announced that Yeshua was going to be stoned because he practiced sorcery and enticed Israel to apostasy.

In this passage, the writers of the Talmud are mostly concerned about the practice of sorcery and enticing Israel to apostasy. They don’t dismiss Jesus as a myth.

In addition, Yeshua’s (Christ) name was mentioned in the following sources:

- “Talmud, the Jewish tradition of the Mishnah and the Gemara”, from The Jewish Encyclopedia (1907 edition), “Sabbath 104b and 116b”; “Sanhedrin 43a, 67a and 107b”; and “Sotah 47a” sections

- “Jesus of Nazareth”, an article from The Jewish Encyclopedia (1907 edition)

- “Jesus Christ and Talmud and Midrash”, articles from The New Encyclopedia Britannica (1981)

- “Jesus”, an article in The Encyclopedia Judaica

Did Jesus Write Books?

Another question the skeptics often ask is, “If Jesus existed, why didn’t write anything?”

Numerous historical figures haven’t left any original writing. Socrates, the ancient Athenian philosopher, only exists in his students’ writings. There is not a single document that contains his original work. However, no one believes that his students all imagined Socrates.

Alexander the Great became the king of Macedonia. He was a handsome, arrogant leader and military genius who moved through the towns and kingdoms of Greco-Persia until he conquered them all. The history of Alexander was collected from a few ancient sources that were written 300 years or more after he died. There are no direct eyewitness accounts that confirm that Alexander ever existed. Despite that, historians are convinced, from archeological findings and his impact on history, that Alexander existed.

The same can be applied to Jesus who is known to the world through the writings of the disciples. Shlomo Pines, an Israeli scholar, and Will Durant, a world historian, both said that no first-century Jew or Gentile ever denied the existence of Jesus. Even the early century skeptics never expressed doubts that Jesus existed.

Many independent accounts prove that Jesus did exist and that he was a historical figure. He existed as a man, his name was Yeshua (Jesus), he had a brother named James (Jacob), Pilate rendered the decision that he should be executed (as both Tacitus and Josephus stated), and his execution was done by crucifixion (according to Josephus).

These various historical sources offer valuable information concerning the life of Christ. They reveal immutable facts that the Messiah was Jewish, healed the sick, preached the gospel of the Kingdom, and was betrayed and crucified.

*As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.